Searching for a Job in Europe

Tips and resources for Americans seeking something better

On the morning I arrived in Amsterdam for a week-long trip, I didn’t have much time for sightseeing. So, I packed my stuff into a left luggage locker (10-20€, next to Amsterdam Centraal) and went for a walk into town.

Around lunchtime, as I was walking along the Herengracht, I came upon a bar serving a wide range of Dutch beers. It was an unbelievably pretty day out, so I opted to drink a “Blonde Enigma” at an outside table (no extra charge).

Next to me were sat a few Americans. That’s pretty typical for a late spring afternoon in Western Europe. But this time the conversation was different. The two couples at the table next to me were discussing options available for Americans to live and work in Europe.

As I write this, I am on a train in Germany, a country I have visited four times in the past year. I know that seems like an excessive amount of travel—it certainly hasn’t been cheap. But when you find a person you really bond with, you want to see them more than four times a year, you know?

But that’s not the only reason I keep coming back.

I’d like to live and (hopefully) work in Germany in the next few years, especially as my kids finish school and leave home for college and their own lives. My establishing a home base in Europe would give my children more options for school, work, love, and life.

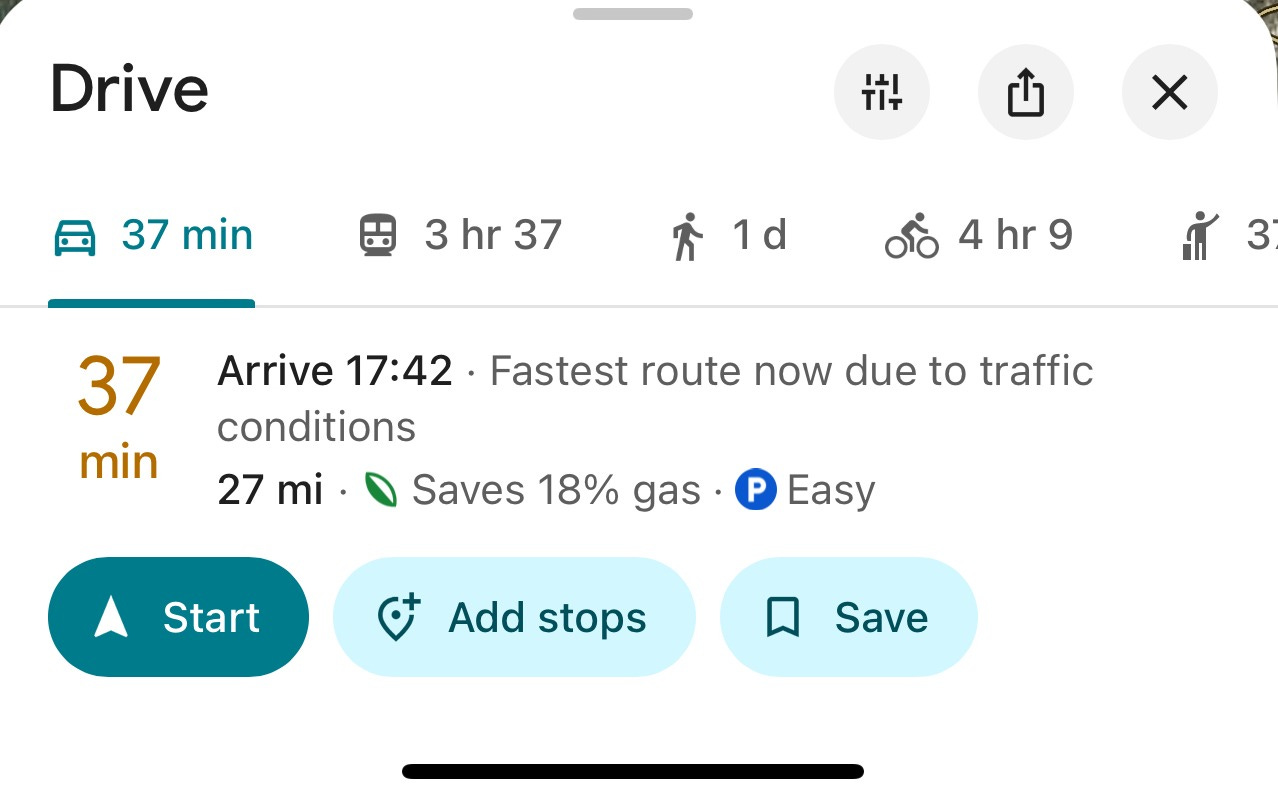

I want to be able to take a train to Paris or across town. In fact, I want a choice of trains—U-Bahns, S-Bahns, regional trains, high-speed trains, trams.

I want to move to Europe on my own merit—not through marriage or blood. Even in The Year of Our Lord 2025, when I ask American peers, both female and male, who live and work in Europe how they do it, nine times out of 10 they will answer, “Oh, because I’m married to an Italian/Spaniard/Frenchman/Belgian.”

F— that.

While there’s nothing wrong with marrying a partner for visa purposes, I don’t want it. Love, yes. But I don’t want my desire to be elsewhere to be something a partner can withhold from me as a means of control.

Been there, done that.

So when I realized1 that I had retained some of the German I had learned as an exchange student 30+ years ago—and that it could be my ticket to new professional and social opportunities—I wanted to hone that skill.

Despite having minored in German at university and earning a Certificate of Translation, I stopped using the language shortly after graduating from college. I felt like I had gone as far as I could with it and I was bored of always talking/reading/hearing about World War II and the Berlin Wall.

Back then, it didn’t occur to me that I could just work a regular job that happened to be in another language. Moving to Europe in those days didn’t seem like a choice I could make or a dream I could dream alone.

Over the past year, however, I realized I could fulfill almost all of the required paperwork for a German work visa. The immigration laws in Germany are currently in flux, as the new, more conservative government tries to peel back some of the immigration reforms the previous Bundesregierung had instated. But German immigration laws are more relaxed than those in Italy, where there are increasingly fewer pathways to residency.2

Germany needs workers, I need work. I am quite possibly a very qualified candidate for a work visa. Maybe I could go back to school in Germany, where university costs next to nil? Maybe I could volunteer for a while as a pathway to establish residency?3

But first, I needed an official certification of my language abilities.

I wasn’t starting from zero. So, as I have done with Italian4, I began reading and listening to more German by tuning in to soccer matches over internet radio; listening to German music; reading and subscribing to German language newspapers and magazines; and speaking German whenever I could. I have also been reaching out to my network to see if any contacts had any ties to Germany and/or an interest in speaking German.

I registered at the Goethe Institut for the B2 exam, a four-module test of the learner’s reading, hearing, writing, and speaking abilities. B1 is the minimum for German permanent residency. But, since I was assessed at B2, so I wanted to try for the harder certificate.

Long story short, I passed only one module and failed the other three by a few points. So, I have a B2 certificate in writing (the hardest module?), but lack certification in the other three disciplines.

Failing individual modules of the B2 German exam does not automatically earn you a B1 certificate; it only certifies participation in the B2 exam. Luckily, you can take each module separately and official German language certification exams are frequently on offer from Goethe Institut and TELC exam centers around the world.

Leaving one’s country to seek a new life and more opportunities is scary and challenging, even when the only barrier you’re dealing with is paperwork. It’s a privilege to have time to consider one’s options. But there’s nothing easy about immigrating “the right way.”

An eager, ambitious, curious, and smart person should be able to find work in his or her own country. But, sometimes countries fail its citizens. Look at Italy and its brain drain.5 Or look at any other nation with diasporas elsewhere.

Lack of job opportunities and no positive vision for the future are what drove my grandparents’ grandparents to leave their homes in Germany, England, Scotland, and France to search for a better life in the USA. My desire to try the reverse shouldn’t seem so far-fetched.

There are so many wonderful aspects to the USA—our national parks, baseball, jazz6—but I know that I’ll never be happy living out the rest of my days in a land where so many people measure progress by whether a town has a Wal-Mart or a Target. I’ve grown tired of a populace “yelling about cultural collapse with a mouth full [sic] of masticated Chik-Fil-A.”7

Many friends, family, colleagues, and strangers can’t understand the contempt with which I hold the country of my birth. But that’s because they don’t know what else is out there. I’ve seen what other countries can do. I know that the U.S. has the money and know-how to be so much more.

When I think about the U.S. these days, I think about what wise friends often say about exes: “If he wanted to he would.”

The U.S. could have built a better society over the last 30 years, one equipped with high-speed trains and universal healthcare and free education through the university level. The U.S. could do a lot of great things—if it wanted to. But this country has shown repeatedly that it doesn’t want to improve—and I don’t have another 30 years to wait for nothing.

Now, as I sit on the train in Germany aware of the too-short duration of my latest visit, I am thinking about how I can speed up this process.

Of course, the solution is to move to Germany. No hiring manager in Germany is going to give me a second glance if I’m not already living in the country and I’m not so special that an employer would pay for my relocation.

Moving to Germany may actually be more economical than visiting every quarter. At the very least, the money otherwise used on flights and hotels could go towards rent.

Moving would also help me avoid those “last day blues” when I inevitably break down sobbing—in my hotel room, on the train, at the airport gate, in the plane—as I come to terms, once again, with saying goodbye.

I’m ready to Get the F— Out. Which brings me back to the chance meeting at the canal-side pub in Amsterdam.

One woman I met is one-half of GTFO Tours8, a Dutch company run by two Americans who were equally fed-up with the attitudes and policies of the USA. Like me, these women want to to live in a land that shares their values.

GTFO has been helping Americans move to Holland since the beginning of 2025. They have also started branching out, finding resources for people looking to move to several other European countries, including Germany.9

I didn’t intend for this post to end like an advertisement—GTFO doesn’t know I’m writing about them. But their website and services may be helpful for those of you who feel frustrated like I do. I may even seek out their services for setting up a business in the Netherlands.

At this point, setting up my own tour or logistics company in Holland seems easier than finding a job in the DC area. In the meantime, writing this newsletter is my full-time job.

With that in mind, I hope you will consider subscribing and sharing.

I hate that humbling feeling of having to hold my digital hat in my hand while asking for money. So, if you can’t or don’t want to upgrade to a paid subscription, I’ve put my Venmo, Cash App, and Paypal links in the footnotes so you can contribute without having to worry about a recurring charge.10

Another way you can help is to keep me in mind should you hear of any jobs where I’d be a good fit—in Germany, remotely, or anywhere. Perhaps you have contacts you could share?

If you have any questions about my journey to obtain a German visa or if you just want to send me words of encouragement, click on the button above and I’ll respond as soon as I can.

Thanks to all of you who keep me going as I try to figure out how best to live the rest of this one wild and precious life.

Love and gratitude,

Melanie

https://www.cnn.com/2025/05/21/travel/italian-citizenship-descent-law-change-intl, https://www.npr.org/2025/06/09/g-s1-71526/italy-referendum-citizenship-meloni

https://www.reddit.com/r/German/wiki/faq/

https://www.italofile.com/learn-italian-online/

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249313674_The_propensity_to_return_Theory_and_evidence_for_the_Italian_brain_drain

https://gtfotours.com

Venmo: https://venmo.com/u/Melanie-Renzulli | Cash App: https://cash.app/$mel8twelve | Paypal: https://paypal.me/MelanieRenzulli